Memories of a student

By Ethan Smith

Published in News on August 28, 2016 1:45 AM

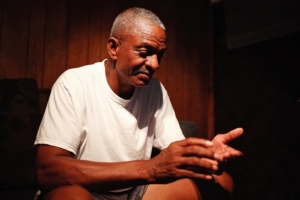

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Channcey Simms looks down at his hands while recalling memories from his childhood as he sits in the den of his home in Fremont -- the home he grew up in. Simms said he remembers looking in the mirror to see what color he was, being outcast from both races as the first black student to attend Fremont School.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Channcey Simms stands in front of the main entrance of Fremont STARS earlier this May after being recognized as the first black student to attend Fremont School. Simms had not been back to the school since leaving as a student.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Channcey Simms talks about the first and only time he used the bathroom at Fremont School. As the first black student to attend the school, he was bullied and pushed around in the bathroom by several students, he then found a place where he could sneak outside to if he couldn't wait until he got home.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Channcey Simms opens the door to what is now Fremont STARS as he visits the hallways of the school he attended years ago as the first black student.

As most children return to school on Monday, their biggest worry might be what outfit to wear or which class will be the most difficult. Those memories will fade.

For Channcey Simms, now 60, his first day at Fremont School was another world and the memories have not faded.

Simms was the first black student to integrate the Fremont schools, and the challenges he faced and abuse he endured throughout his primary education have left a lasting effect on his life.

As Simms stands in front of what is now Fremont Elementary School for only the second time in nearly 50 years, his hands rub together, his eyes gaze at the door of the school and then back to the road. He seems hesitant to go inside -- not unlike his first day in 1966.

His memories from all those years ago ricochet around his mind -- just as he was ricocheted like a pinball around a circle of older school boys in the school's bathroom the first time he used it.

"I wish I had never came here," Simms said, standing outside the school entrance. "This place right here has built up so much aggression in me. I learned how to just soak it in, absorb it. Just take it, take it, take it. Cause I was little, and I couldn't let it out because I was a child."

Simms was only 10 when he began attending school in Fremont, and at the time, what was then named Fremont School was for all grades, from first through 12th.

According to Simms, there was a man that lived on the corner across from the school who had threatened to shoot the first black student who dared to attend the school. The man died the year Simms was to attend Fremont School.

"It just brings back a lot of memories, a lot of bad memories. I had some good memories, but nine times out of ten, they were bad memories," Simms said, walking through the school's silent hallways. "You know, at 10 years old, I stayed scared most of the time. I couldn't go to the bathroom. I could, but I didn't want to. It was just this one building with 12 grades. So if I go to the bathroom, I'm in the bathroom with the big boys. I was subjected to being pushed, kicked, all kinds of name calling -- just a lot of abuse."

Darron Flowers, now the mayor of Fremont, was the superintendent of the Fremont school system in 1966 and he was also principal of the school.

Simms attended Fremont Friendship Elementary School until the third grade. He said his mother could see Fremont School from their front porch, and after a year of him having to get up at 5 a.m. to ride the bus to school, his mother decided to send him to what was then an all-white school.

Flowers said the school received no special notification of Simms' enrollment, but that it effectively desegregated the Fremont school system, which had been required by federal law.

"The office of civil rights, which was established for the purpose of desegregating schools, or that portion of it, had several ways you could comply with the fed guidelines," Flowers said. "One was freedom of choice, and it was exactly that -- if you lived in a majority-minority school, you had the freedom to choose any school you wanted to, so Channcey chose through freedom of choice the Fremont School, and once he chose it, he enrolled just as any other kid would have. There was no special enrollment process. His parents, when they enrolled him, you knew he was going to be the first black kid that was going to be there."

It was not an easy time for the boy.

Sims said he was physically and verbally abused by fellow classmates because he was the only black student.

"My sixth grade teacher, she didn't tell me in so many words that I needed to be back out in the woods with the rest of the blacks, but I understood that she didn't care nothing about me," Simms said. "I had a few real racist teachers. It wasn't nothing out there, but you can tell at a young age when somebody doesn't care for you and doesn't want nothing to do with you."

Simms recalls one story of when he broke a white boy's arm accidentally while playing a game during recess after one of the white children tripped him and Simms slapped him in turn. Simms said one of the boys held his arms behind his back so another child could hit him, and Simms said he spun around and broke the other boy's arm. He was not punished, but the fear of retribution stayed with him for a long time.

Simms said there were many similar incidents that kept him scared, from older boys pushing him and beating on him in the bathroom to a girl slapping him for tapping his pencil on a desk.

"I wasn't scared for my life, but I was just thinking about how I was going into the unknown, the outer limits," Simms said. "But I knew I had to make it. I had to do it."

On top of Simms being the first black student at the school, his father, Delay, was the first black police officer in the town.

Simms' parents always saw to it that he dressed well and even that got him into trouble with his black friends.

"It was disheartening. A lot of times I didn't even want to come out -- I had to deal with it on the black side too as much as the white people, too," Simms said. "The black people felt like I thought I was better than them."

One of Simms' former classmates and longtime neighbors, Melody Boyette-Hendricks, described how much abuse Simms endured from all sides.

Boyette-Hendricks said she went to Friendship Elementary School with Simms, was a classmate through the third grade with him and then lived in the same community as Simms until the age of 14.

"I just remember him having to almost fight the kids because they were just so cruel to him," Boyette-Hendricks said. "They just thought his parents thought he was so much better than everyone, so they bullied him, and it was really sad because he didn't have good friends like all of us did. I just remember how badly he was bullied, even in our community. The kids didn't know any better because we had never been to school with white kids."

Boyette-Hendricks said she and Simms became fast friends and have remained so ever since. But she said she can see the lasting effect that Simms' schooling has had on his life.

"It's just amazing throughout his whole life from the discrimination he got from the teachers and the children, and I remember how unhappy he was as a kid, and the toll it took, and the scars it left on his heart and mind that lasted into adulthood," she said.

Simms said one of the biggest things that has stuck with him is how long it took for him to be formally recognized as the first black student to integrate Fremont schools. He said he never sought any kind of recognition, but that finally being recognized this past year for what he went through has helped him begin healing the wounds he still carries.

Simms was honored for the first time in February at the annual Human Relations Awards Banquet held at Herman Park Center.

"Channcey and his family are to be commended," Flowers said.

"Because it took a lot of faith to make that leap with your child. When we look at Channcey today, we lose sight of the fact that he was a small kid when this took place."

Simms stands in the middle of one of the classrooms he was taught in 50 years ago.

"Jesus," Simms said softly. "Still looks the same though. It's making my ears ring."

Now, as Wayne County schools prepare for the first day of class, Simms looks back on his leap forward with a quiet sense of pride.

"Right now, it's just a sense of pride that I was able to withstand something like that at such a young age," Simms said. "I feel disappointed that it took so long for somebody to realize or even, I don't know the word to use -- that somebody would, you know, bring it up, recognize what I went through. It was trying. For somebody to have to go through that, like I said, I wouldn't put it on nobody. But I wouldn't want to do it over and change it. Would I put my child through it if I had to? I don't know. In the long run, I guess it all depends on the individual as to how it affects you."