Being the first

By John Joyce

Published in News on February 14, 2018 5:50 AM

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Ernest Lofton talks about some of the items on display at the Wayne County Museum recognizing his business as the first black portrait studio in Goldsboro.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Ernest Lofton demonstrates how to load film into the Speed Graphic camera he once used to take photos. Each loader could only hold two pieces of 4x5 film.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Ernest Lofton holds a photo of himself from 1958 as a young man processing film.

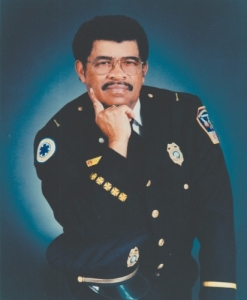

Ernest Lofton poses for a photograph in his fireman's uniform.

Ernest Lofton's father served in World War I.

Three of his brothers fought in World War II and two others in Korea.

Yet, during their service and for much of their lives after, none of them would have been permitted stand where he is now.

During those times, what is now the Wayne County Museum was the USO club, where veterans of those conflicts could congregate ---- if they were white.

"The black soldiers, they would have to go to one of these houses around here, you know."

Lofton, 81, described how some of the houses down behind the museum were lived in by black families, many of whom may have had one of their own serving during one conflict or another, and that is where black men who served could get together freely and hang out.

Amid the display cases surrounding him, Lofton points to different photos ---- many of them he'd taken ---- of people he knew. Also on display are some of the cameras he used during his decades in business operating Goldsboro's first black-owned photography studio and photofinishing shop.

"I still am the only one. I don't know of any other black photography studios around. Do you?" he asked.

As he talks, Lofton pulls out a sheet of hand-drawn schematics for a full deck being built onto the back of one of his rental properties.

He drops onto the glass top of one of the museum cases a photo of his younger self, nearly 60 years ago, hard at work in the photo shop where he held his first real job.

"This was in Mr. Nelson's shop, here. In fact, that's what I was doing there was making a copy," he says, pointing to himself in the photograph marked "1958."

"I treated him kind of bad there a little bit but he was a good guy. He paid me great money," he said.

•

Lofton first went to work for Earl Nelson at Nelson's Photography Studio in downtown Goldsboro in the mid 1950s.

At just 12 years old, Lofton's older brother, who also worked for Nelson, was able to get him a job there sweeping up the floor and taking out the trash.

"That was at 118 Center St.," he said.

What is a row of boutiques now used to be the photo shop, sandwiched in between the old Goldsboro Hotel and what was once a Western Union and a drugstore. Later on, when the druggist passed away, Nelson moved his studio over to that building, Lofton said.

After a while, Lofton was sweeping up the whole row.

Lofton said he stopped into one of the stores along the strip recently and asked if he could look around. One of the floors in the back that used to be his old workspace, a darkroom and an area for developing and finishing photos, still had the chicken wire floor that he would have to mop.

"She said there was some tile there that had been taken up," he said of the present owner. Underneath it was floor Lofton came to know so well more than half a century ago.

As Lofton came of age, he learned more about the photo business, the machines used then to develop film, finish photos, make copies.

He describes the process of running strips of wound up film, hung in individual rows of 10 on racks four and five at a time, and dipping them at once into a solution that would bring the photos out.

"So that's 40 at a time, 50 at a time," he said. A lengthy, painstaking process. But then, Lofton is no stranger to hard work.

In addition to establishing his own photofinishing business ---- he worked for decades as a photographer himself, shooting bridal portraits, weddings, events, even crime scenes for local attorneys ---- Lofton is also a retired Goldsboro city firefighter. He was among the first five or six hired on, he said, and later became the first black firefighter to drive one of the city's firetrucks and only the second to be promoted to officer.

He understands and can recreate simplified plans from an architects blueprints. He did the work, he said, on more than 50 percent of his own house.

He also owns rental properties and was, with a partner, the designer and owner of the Webtown mini-mall in the area of Slocumb and Elm streets back in the early 1980s.

But before all of that, going back to sweeping up the floor of Nelson's studio, Lofton was a budding entrepreneur.

•

Back in those days, a quarter could get you a popcorn, some candy, a drink and admission to the movie theater. And since they didn't kick you out after the show was over, you could stay there all day long.

"Because, they didn't ever chase you out of there," he said.

So, once Lofton went to work for Mr. Nelson, that's what he and his friends would do.

He set about sweeping, and quickly graduated to taking the "quick photos" outside the store. People passing by could stop and have their photo taken. Nelson would then take it into the back and his brother would develop it, and Lofton would bring it back out to them.

Years passed and Lofton developed a broader skill set. His brother moved on to other things, but Lofton stayed on, working for Mr. Nelson.

And business was good, especially when Seymour Johnson Air Force Base got up and running after being shut down for a number of years.

Once that happened, Mr. Nelson got the base contract to develop photos for the base and all its servicemen returning from deployments around the world.

Lofton had by then started working at Cherry Hospital as well, earning about $150 a week he said.

Mr. Nelson, needing full-time assistance, asked Lofton to come on permanently.

"He asked me how much I was making. And me, I'm always thinking ahead, I told him $200 a week. He said 'I'll double it.'"

Business boomed for the next couple of years.

"We were the only photofinishing company around, so Mr. Nelson didn't have no competition, see. So we got that base contract, that tripled our orders for photofinishing work," Lofton said.

Things stayed pretty steady for Lofton after that, until, in the early 1960s, color film started to come in. Nelson, Lofton said, didn't want to invest in the new equipment necessary to handle processing color film, but he didn't want to lose Lofton either.

Knowing he could not continue to afford to pay Lofton what he had been making up to that point, Lofton said Nelson decided to do him one better.

"He said, 'Why don't you let me get you on to the fire department?'" And Lofton agreed.

The fire department by that point had been integrated, Lofton said. And aside from the benefits and regular pay, there was an added incentive. Firefighters at that time worked 24-hour shifts, one day on, one day off.

That meant Lofton could work a full shift with the fire department, whether there was a fire to fight or not, and then have the whole next day to work at the photo shop.

"We worked like that for a pretty good while, so Mr. Nelson said well look, 'You can still do my work' ---- he knew I worked pretty good ---- 'Plus you're going to have benefits and retirement.'"

Lofton met with his share of resistance, being a black man on the mostly white fire department.

He tells about having to deal with the use of the "n" word from time to time and other instances when he felt he was being slighted because of his skin color.

But because of his connections with Mr. Nelson, all of the affluent people around town knew Lofton, he'd been in their homes delivering photos or taking them, he knew who to go see when things got out of hand.

Plus he'd been a lifelong member of the NAACP.

"They knew I wasn't the one to stand there and take that foolishness," he said.

On more than one occasion, he had to enlist the help of friends, such as the would-be Mayor Hal Plonk, to sort out scrapes or ruffled feathers inside the department.

He said at one point, he guesses because they wanted him out of their hair, the higher ups at headquarters stationed him out at the fire station over on Beech and Madison where it would be just him and one other guy.

The other guy, he said, was known to be one of the most bigoted guys around.

"See, they were expecting us to fight. We got over there and I said to him, 'You know why they did this don't you,' and he said, 'Yeah,'" Lofton said.

The men didn't fight. Instead they became lifelong friends.

By 1970, Lofton had learned enough and saved enough that he wanted to strike out on his own. He went to Mr. Nelson and told him he was going to open his own business.

"It had been on my mind, that's when I decided to go on my own," he said.

Nelson did not have much of a reaction.

"His wife, Mrs. Nelson, she was tickled to death, she said 'Ernest, it's about time.' And that was kind of strange. Earl, he was just kind of, he just kind of laid back. She said, 'I hope you (have) good luck.'"

Lofton told the Nelsons he would still be happy to do some of their work, but not for the money he'd been making before.

He paused and raised his index finger.

"For a percentage," he said.

Lofton's Photo Studio opened in 1970. He prospered in business but needed his own location. And when it came time to scout one out he knew just where to go.

"On the corner of Slocumb and Elm. There was a Power Five and Dime over there," he said.

Mr. Power offered Lofton the building that is today the Islamic Center at the corner of Slocumb and Elm, but Lofton thought the parking there was too limited.

Across the street sat an old furniture store which had lost its following when the new mall had begun to see more activity.

So he got together with a friend of his, Patrick Best, who happened to be the first black principal at Goldsboro High School, and the pair went into business together.

"I drew the plans how I wanted, we were going to have an adult lounge in the back, have a restaurant up front on the other side. We were going to have an eating room in the center and then we were going to have a beauty shop in the back," Lofton said.

And that became the Webtown mini-mall. The lounge was called the Pink Panther Lounge, Lofton said. The beauty salon was called A Touch of Class.

"The beauty shop is still there," he added.

•

Today, with many of the cameras he used and photographs he has taken throughout his career on loan to the museum for its Black History Month exhibit, Lofton busies himself with his rental properties and handiwork.

He has a work space in the back of his house with every kind of tool you can imagine, he said. He also has a wall of write-ups and citations for the lives he saved and good works he performed as a firefighter.

He looks back on his years working for Mr. Nelson and the fire department as successful, despite some of the conditions a black man faced during segregation and integration. He said he never worried too much about the consequences of standing up for himself.

"I wasn't worried about my job," he said. "I can get a job."