Survivor's story: J.L. Wilson, 98, shares his first-person account of Dec. 7, 1941

By Steve Herring

Published in News on March 25, 2018 3:05 AM

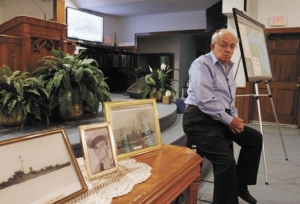

News-Argus/STEVE HERRING

J.L. Wilson looks at photographs taken during his service in the U.S. Navy during WWII. Wilson was serving aboard the USS Dale, stationed at Pearl Harbor on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked.

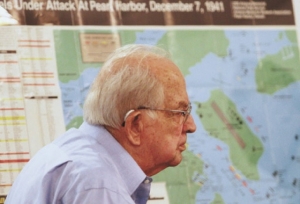

News-Argus/STEVE HERRING

A chart indicating the position of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor the morning the Japanese attacked in 1941 is displayed by survivor J.L. Wilson, 98, of LaGrange.

Dec. 7, 1941, started off as just another Sunday morning in paradise.

J.L. Wilson, a 22-year-old petty officer 3rd class from LaGrange, had just finished his morning chow aboard the USS Dale, a Farragut-class destroyer moored at Pearl Harbor.

Now at 98, Wilson, is one of the few remaining survivors of that day of infamy.

Wilson shared with an audience at Woods Grove Church Wednesday night his wartime experiences.

He even set the backdrop for the attack, outlining Japan's growing aggressiveness as it sought to take needed natural resources by force.

Wilson grew up during the Depression, graduating from high school in 1937.

President Franklin Roosevelt was trying different things to jump-start the economy, one of which was the Citizen Military Training Corps, he said.

Teenage boys would go to Fort Bragg for two weeks to learn about Army life and earn a little money.

"I went to Fort Bragg," he said. "Second day, the sergeant came out in a vehicle loaded up with shovels and headed into the woods. He told us to lay on the ground -- 'make a mark at your head and a mark at your feet.'

"'Between those marks you will dig a hole. This is where you will sleep tonight.' I stayed a week and decided I didn't want to sleep in foxholes."

However, Wilson said he still decided to join the military because there were no jobs, and he did not have the money to go to college.

"So I picked the Navy in 1938," he said.

Join the Navy and see the world -- seemed like a good idea at the time, he joked.

He took his training in Norfolk, Virginia, and was assigned to the USS Dale.

In 1939, Japan was "sort of raising its feathers" and the decision was made to beef up the U.S. naval presence in the Pacific, he said.

That included eight battleships, three aircraft carriers, two heavy cruisers, four light cruisers and 36 destroyers.

In late November, 1941, a Japanese fleet that included several aircraft carriers left Japan.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the task force took position 200 miles north of Oahu to launch two waves of aircraft to attack Pearl Harbor.

The real prize, the U.S. fleet's aircraft carriers -- the Lexington, Saratoga and the Enterprise -- were out at sea at the time of the attack, he said.

So the next biggest targets were the eight large battleships moored in the harbor.

The Japanese failed to destroy the large fuel farms near the harbor, and many of the ships that were badly damaged were quickly repaired and back with the fleet within three months, he said.

Prior to the attack, a radar unit on the north side of the island detected a flight of aircraft. The operators called it in, but were told not worry, he said.

The leadership thought the radar had picked up a flight of B-17 bombers that were expected that day at Hickam Field near Pearl Harbor.

"But what the radar picked up wasn't B-17s," he said. "It was 147 planes from the Japanese carriers."

It was 7:55 a.m. Hawaiian time, 12:55 p.m. Eastern time, he said.

As was customary, half of the Dale's crew was onshore, and the other half, including Wilson, who was a torpedo man, was still aboard ship.

"The Navy doesn't have breakfast," he said. "They don't have dinner, lunch, supper. It is all chow, regardless of what time of day it is.

"At 7:55, we were finishing up. I went topside. The first thing I saw -- hangars on Ford Island, all of them in flames. Japanese planes, I didn't know who they were until I saw the red ball (markings).

"At the same time, I looked toward the Arizona."

The battleship's band was lining up on the stern of the ship getting ready to play colors at 8 a.m., Wilson said.

"I saw them," he said. "While I was looking, a bomb hit on the stern of their ship and knocked some sailors flying into the ocean, on fire."

Wilson went to his battle station as the Dale made way to leave the harbor -- one of the first ships to escape to the open ocean.

"We got under way," he said. "We were under attack. A dive bomber dropped a bomb, but it missed us. The bomb hit the bottom and exploded.

"We were the second ship out and we thought the whole Jap fleet was sitting out there. Clear ocean. There was not a thing in sight except for clear water."

It was not Wilson's only brush with battle.

While serving aboard the USS Whitehurst, a Buckley-class destroyer escort, the ship was struck during a kamikaze suicide attack during the Battle of Okinawa.

"We shot down four planes that day," he said. "But the fifth plane got through. There was a Navy fighter plane chasing this particular plane. He would have shot him down if he had time."

But the pilot did not want to get hit by gunfire from the ship so he pulled off, Wilson said.

The kamikaze hit the bridge structure.

Three men jumped off the bridge and into the ocean

As the ship executed a turn to port (left), one of Wilson's shipmates kept watch to see if any of them surfaced.

The man watched the ship's wake and saw the water turn red.

Those three men are still listed as missing.

"We lost 47 men in that attack," Wilson said.

It was later determined that the kamikaze pilot was 17 years old, Wilson said.

Wilson, who left the Navy after eight years, said he has no animosity toward the Japanese.