A soldier's guard and honor

By Steve Herring

Published in News on January 31, 2018 5:50 AM

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Daniel Boyette talks about his service in U.S. Army and guarding John F. Kennedy's grave before the eternal flame was added.

Submitted photo

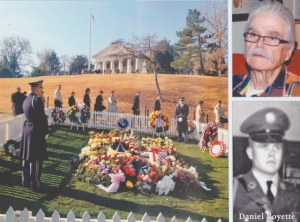

A collage that was developed by an Austrian who identifies himself as Peter Schittler who wanted Daniel Boyette to autograph.

Submitted photo

Daniel Boyette, right, stands for an inspection while he was serving in the Army.

Daniel Boyette was just out of high school, in the U.S. Army and scared.

After all, the 18-year-old was standing guard duty alone at night.

With an unloaded weapon.

In a cemetery.

During the dead of winter.

It wasn't until later that Boyette, now 73, fully realized his role -- during some of the darkest days in U.S. history -- as one of the men who stood guard over the grave of President John F. Kennedy.

Boyette, of LaGrange, was raised in Goldsboro and graduated from Goldsboro High School in 1963.

"I enlisted Airborne and went through Airborne training," he said. "I get ready to leave Fort Benning (Georgia), and they sent me to Arlington (Virginia), and I never saw another airplane so I don't know, I can't explain that."

He arrived in Arlington in early December 1963, from Fort Benning and ended up in Headquarters Co. There he worked as a truck mechanic serving his three-year hitch.

"When I wasn't doing that I was doing funerals in the cemetery, doing parades," he said. "I helped in Gen. (Douglas) MacArthur's funeral. I was standing guard on Constitution Avenue."

During the day, a guard from a special detail stood watch over Kennedy's grave before the eternal flame was added.

"I just did it at nighttime," Boyette said. "This lasted for probably between two and three months. Then, when they put the eternal flame there, the guards, except during the daytime, went away. I am not sure today if they have a guard stationed there. You had shifts. You had like two hours on and four hours off. It was all night alone. I think overnight I would maybe do it twice -- two two-hour shifts.

"But it was in the rain, in the snow, whatever was going on. It is pretty cold in D.C. in January and February. The biggest thing I remember, the thing that most stands out in my mind, is all the different sounds that you can hear in a cemetery at night. I mean limbs falling, whatever kind of crackling that is going on. You're supposed to be there by yourself, but I really don't think I was there by myself. I heard all kinds of sounds. You couldn't see it to know what it was."

He had a rifle, but it was ceremonial and was not loaded.

"I did learn later there were exactly 100 (who stood guard), and there was a list of the names I saw one time," he said. "I Google searched it and it came up... and my name was on it."

Boyette said he has been unable to find that list again.

"I was 18 years old, and when you are 18 years old, in a situation like that, you are about half scared anyway," he said. "I mean, you don't know what's happening. I am 73 today so that was a long time ago.

"I was proud to do the duty. At first, I didn't like to do the duty -- all the spit and polish. Every 't' had to be crossed and 'i' dotted. It was really, even in your sleep I felt like if I moved and wrinkled a sheet I was going to get scolded by the sergeant. It was really kind of scary. It is history. It truly is history."

But at the time Boyette said he did not realize the historical aspect.

"No sir," he said. "I was 18 years old, right straight out of Goldsboro High School. Until I went to Fort Myers at Arlington, I hadn't even heard of the place. Eventually I realized where I was and what was going on."

Boyette also remembers that during his time there an alert was issued for units all around Washington, D.C.

He said the leadership did not tell them what the alert was about.

The soldiers were called to stand guard at all of the national monuments.

"I was at the Lincoln Memorial standing there with a fixed bayonet walking," he said. "Had no idea of what I was supposed to be watching for. They don't tell you anything. That was probably a couple of years after I had gotten there that that happened."

It is an honor to be a soldier in the U.S. Army, regardless of what detractors might say, he said.

His memories of that time surfaced last week after he received an envelope from a man in Vienna, Austria.

It contained a letter, two sets of photos of Boyette today and as a young soldier and a photo of Kennedy's grave with a guard and sightseers.

It also included a new $5 bill for return postage and a postcard of Vienna.

"I saw the return address, Vienna," Boyette said. "The first thing I thought it was something off the wall until I opened it and saw my picture."

The package is from a man who identifies himself as Peter Schittler.

In his letter, Schittler refers to himself as a history buff trying to learn more about that era in U.S. history. He said he decided it would be a "coronation" of his studies to try and find some of the people who were actually there back then.

He said he found Boyette's name through a TV video about an eastern North Carolina man who guarded Kennedy's grave.

He said he looked the name up in an online phonebook.

"I enclose a simple collage I made and would feel honored if your time allows to sign it for me, on the front, please," the letter reads. "While I know that it isn't anything new to you, I still enclose an extra (copy of the photos) for you to keep."

Schittler wrote that the assassination of Kennedy and the events that followed mark one of the darkest chapters in U.S. history.

"I remember my parents (I was only born in the early '60s) later told me how shocked they were -- a generation that emerged on the ruins of the war looked over to America as the home of democracy where you vote people out of office, but don't kill them," he wrote in the letter.

Schittler said he is not a conspiracy theorist, but simply wanted to be better informed about that period in U.S. history.

He searched online, but could not find out anything about the man other than two articles, one concerning a Vietnam-era soldier and another from World War II that the letter writer had sought out.

However, Boyette said he is still not 100 percent sure it is not a scam of some sort, and is uncertain what his response will be.

"It's just an oddity story that certainly doesn't happen every day," he said. "I know all of that about me is correct, but I don't know about the other part.

"When you don't know about things, all kinds of things can pop up in your head, especially in today's world. It is much crazier than it was when I was coming up, or at least I think."