The Casualties: The antidote - Narcan, a savior or a crutch?

By Ethan Smith

Published in News on December 6, 2017 5:50 AM

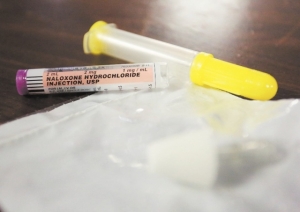

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Pictured is a 2 mg dose of Narcan that is administered by an atomizer, 1 mg in each nostril.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Shoot it. Smoke it. Snort it.

Each plunge of the needle, draw into the lungs or sniff of the powder is an effort to chase that same elusive high -- the one the addict got the very first time they ever experienced it.

But every party ends.

That high they are chasing is a race they can't win.

The addict's body builds up a tolerance to the drug. And so the doses get more potent.

The addiction kicks in and so the chase is on again.

And, invariably, the user overdoses.

The only hope is that somebody gets there in time.

Lately, though, victims are being discovered everywhere -- in hotels, in churches, in public libraries and even in moving cars.

Their skin is purple, blue or ashen; their respiratory rate is dangerously low.

Opioids work by blocking the pain receptors of the user's brain and in turn, the breathing slows, and less oxygen gets to the brain and to the vital organs.

The victim goes unconscious.

EMS personnel and law enforcement respond and hit the victims with the only known antidote -- Narcan.

The Narcan, otherwise known as naloxone, acts to reverse the overdose symptoms and revive the user.

Without it, the victim likely dies.

And when word gets out that there is a batch of heroin causing mass overdoses on the street ---- that "stuff that just might kill you" ---- addicts flock to it.

To a junkie there is no greater draw, despite its lethality, than a more potent high.

•

As of Nov. 16, Wayne County EMS had administered Narcan 210 times this year. The medication is administered by an atomizer into the victim's nose, or from a vial, and works to reverse the symptoms of an overdose.

In October, EMS personnel say they were treating anywhere from five to six overdoses per shift.

"Last year, in the September/October time frame, all of the sudden we had a big rush of heroin overdoses in the county," said EMS Manager Brian Smith. "That's when the first major uptick took place. And now, as time goes along, you can tell when a new batch of heroin comes along because we'll go from a few here and there, and then all of the sudden it just kicks back up. We're in that right now, where just about every day we're having overdoses."

EMS personnel now keep a stock of two Narcan doses on each of their 10 trucks and three quick response vehicles. And day in and day out, across all three shifts, they are treating multiple overdoses per day.

The county's medics began carrying Narcan in 1995. But now county law enforcement is being equipped with the overdose combatant as well.

"...We have just started training law enforcement on it this year because of the increase in overdoses," said Emergency Services Director Mel Powers.

Powers said emergency personnel replenish a deputy's stock anytime Narcan is used by a deputy.

As of Nov. 20, the Office of Emergency Services had 30 doses in the office supply and was keeping two doses per vehicle. Narcan costs approximately $38 per dose, and OES purchases an average of 30 doses per month.

Due to the increased number of overdoses, EMS personnel started keeping bags strictly for Narcan kits. And they are restocking their rigs with Narcan daily.

•

The dosage of Narcan required to bring somebody back from the brink of death is climbing. That is due to the potency of the batches.

These days, heroin is often mixed with fentanyl, carfentanil ---- invented as an elephant tranquilizer ---- and other high-potency opioid derivatives.

The combination makes the drug stronger and potentially lethal.

"A person is used to a certain dose of heroin," said Paramedic Natasha Kelly. "And they take that same dose of this new stuff, and that's what gets them. That's what makes them stop breathing and even die, is not being used to such a strong dose of heroin."

Where EMS personnel used to administer one milligram of Narcan by using a nasal atomizer, the average dose to revive someone now is four to six milligrams. One victim took 10 milligrams to bring back.

"It's never gone back down," Kelly said about the number of overdoses. "It'll just have spikes that are higher, then it'll go back to a normal, which is still high at two to three a day. There was at least five to six every day, every shift, and then spikes on the weekends, and there would be two or three patients we couldn't get back. We were having a lot of people dying from it and there was nothing we could do."

Back when a paramedic was able to administer half to one milligram of Narcan to an overdosing patient and revive them, the impact was immediate.

"It was, 'Oh, I'm fine, I didn't take anything, everything is OK,'" Kelly said.

"Now you give them the increased stuff and have to bag them -- breathe for them -- in order to get their respiratory drive back up, and they're still just groggy."

•

The Wayne County Sheriff's Office equips its deputies with Narcan.

Deputies attended training on how to use it the inhalant back January and February, and it was first issued to them for carry on April 1.

Deputies used it almost immediately. Narcan was administered twice in April, and both times it was able to bring the overdose victim back to consciousness.

Wayne County Sheriff Larry Pierce said he made the decision to equip deputies with Narcan in an effort to save lives, but he recognized some drawbacks to making Narcan so easily available.

"We're in the business of saving lives, protecting life. That's basically what I made my decision on. But it is a two-edged sword," Pierce said. "You have to realize that it is now becoming a crutch for people that are overdosing. They know that, most likely, we're going to get there quick enough to revive them. And now I don't know if they have any fear at all in the drug."

Less fear in the addicts and the more potent batches being sold are proving to be a deadly combination.

"We're seeing so many of the contaminated batches of the heroin that is causing so many problems, because as you know, fentanyl can be anywhere from 50 to 100 times the effects of morphine, and you don't know how much fentanyl you've got in a batch."

Detective Sgt. Chuck Shaeffer said the sheriff's office has seen one individual overdose and be brought with Narcan six times.

Pierce said the agency was first paying about $70 to $80 per dosage unit for Narcan, and recently was able to find some through OES for about $50 a dosage unit.

The Goldsboro Police Department, on the other hand, does not equip its officers with Narcan.

Goldsboro Police Chief Mike West said his department has discussed supplying officers with Narcan, but his concern centers around two issues ---- liability and cost.

West said he is worried equipping his officers with Narcan could give addicts a sense of security, in that they can overdose without fear of not being revived.

Add that to the recurring cost of keeping officers equipped with Narcan, and how supplying police with the opioid overdose antidote would be funded. It further complicates the issue.

"Ultimately, it comes back to our job is to protect people and save lives," West said. "You're just kind of in the ethical dilemma in the middle -- in the end, it's a financial burden that I'm not sure we can sustain. And if we do try to sustain it, is it going to take money from other areas of the department that I could use for drug enforcement to try to get a handle on that? Or government-wise, could they be spending their money in a different area to put more programs, intervention and treatment facilities in place?"