Part I -- The Casualties: A look at the numbers - Overdoses and deaths

By News-Argus Staff

Published in News on December 6, 2017 5:50 AM

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Wayne County Health Director Davin Madden listens during a community meeting in November about the opioid crisis.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

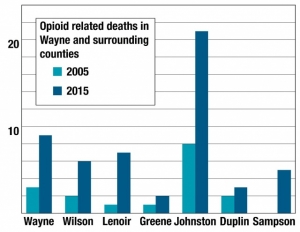

A graphic showing a comparison of opioid related deaths in Wayne County to neighboring counties.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

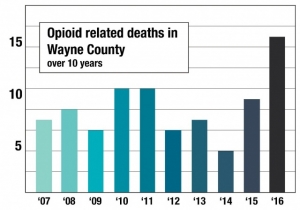

A graphic showing a comparison of the number of opioid-related deaths in Wayne County over a 10-year period.

News-Argus/CASEY MOZINGO

Deaths from opioid-related overdoses are now the leading cause of accidental death in the United States. The drugs are increasingly claiming lives across the nation, state and in Wayne County.

While the number of deaths in Wayne County is lower than other larger North Carolina cities, the increasing trend of overdose deaths is significant, officials say.

"When we have lost one person, that's too many to drug abuse," said Davin Madden, director of the Wayne County Health Department.

"We have seen, even in Wayne County, the number of deaths have increased fairly dramatically, even though the statistic is low."

Drug overdose deaths from opiates are higher in more populous North Carolina areas, including Wake, Mecklenburg and Forsyth counties.

Opioids are a class of drugs derived from opium that interact with opioid receptors on nerve cells in the body and reduce the intensity of pain. Because they produce euphoria, they can be misused, Madden said. Opiates include heroin, synthetic opioids like fentanyl and prescription medicines, including oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine and others.

A PATH TO HEROIN

In an effort to crack down on the opioid epidemic, North Carolina passed HB243, also known as the STOP Act. The law places new restrictions on medical providers who prescribe opioid drugs ---- like morphine or oxycodone ---- and requires electronic prescription filing.

Providers are required to check a state database to reduce the amount of opioids prescribed by medical professionals.

"We all know from research that, specifically, those that have addictive personalities, they can be addicted only after three to 10 days of continual use," Madden said. "We were creating some of our problem from our prescription opioids, just because of our prescribing behavior. We were overprescribed."

When the medicines are no longer available, many switch to heroin.

"That's where it starts, typically," said Julie Henry, vice president of communications for the N.C. Hospital Association. "They get addicted and then they can't get them and they go to heroin.

"There is a need for the feeling and so heroin is the option. Heroin is an alternative and that's one reason. Heroin is also easier to get than prescription pills."

According to the N.C. Department of Justice, 82 percent of heroin users used prescription painkillers before heroin.

'NOT EXCLUSIVE

TO JUNKIES'

In North Carolina, more white men, between the ages of 20 and 50, are dying from opioid-related overdoses. In Wayne County, the deaths in 2016 included primarily white men and women, anywhere from age 20 to 55, according to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

The deaths fail to show how widespread the problem is, Henry said.

"Opioid addiction is not exclusive to junkies," Henry said. "It's happening to upper middle class teenagers. It's happening to middle class moms and even seniors. It's not exclusive to any age, race or socioeconomic class of people."

The number of opioid-related overdose deaths has increased during the past decade, with increasingly higher numbers in recent years.

More and more people are also dying from heroin overdoses and overdoses that include fentanyl, an illegal, lab-made synthetic opioid with 50 to 100 times the potency of morphine.

For drug users who have built up a tolerance to a certain drug, fentanyl can produce the level of euphoria they're seeking. It can also further drive their addiction, Madden said.

"I think that's why it's popular is because the fentanyl is potent," Madden said. "It drives a very potent high. If you're an opioid user and you're getting a duller and duller experience due to some level of tolerance, then there's only two ways to experience a better high -- get stronger stuff, or detox yourself so you lose that tolerance level and start over again. Most people will seek stronger stuff."

INCREASING

OVERDOSE DEATHS

In Wayne County, the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services reports that three people died from an opioid-related overdose in 2005.

By 2015, the number of deaths increased to nine. But within those years, there were fluctuations in overdose deaths, including four in 2006, eight in 2010 and seven in 2013.

The increase in Wayne County deaths follows a similar trend as the state. In 2005, 642 people died from opioid-related overdoses in North Carolina. The number of deaths almost doubled within a decade to 1,110 in 2015.

Even more people died in Wayne County in 2016, with 15 recorded deaths resulting from opioid use, according to the state Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there were close to 33,000 opioid-related overdose deaths across the nation in 2015 and nearly 64,000 in 2016. This has resulted in an increased urgency by federal and state leaders to seek solutions, including a crackdown on prescription pain medications.

Limiting the prescriptions is also driving people to find alternatives, Madden said.

"As you crank down on the prescription issue, you're going to drive people to the illicit market," Madden said.

HEROIN,

FENTANYL USE

During at least the past year, toxicology reports show an increase in the number of opioid deaths that included the presence of fentanyl.

In 2012, 2013 and 2014, one person per year died in Wayne County from an overdose that included the presence of fentanyl, according to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. By 2015, fentanyl was a contributing factor in three of 10 opioid overdose deaths.

By 2016, seven out of the 15 opioid overdose deaths in Wayne County included the presence of fentanyl, reports show. One of the deaths was due to the use of fentanyl alone, while the others included a mix of drugs such as fentanyl with oxycodone, fentanyl with heroin and fentanyl with cocaine.

Heroin played a greater role in the 2016 deaths, with heroin being a contributing factor in 11 of the 15 overdose deaths in Wayne County.

Statewide, there were 479 fentanyl or fentanyl analogue-related deaths and 521 heroin-related deaths in North Carolina in 2016, according to the state medical examiner.

LOCAL PROGRAMS,

SOLUTIONS

Federal and state government leaders are grappling with answers to what has become a complex epidemic that has evolved for years.

Families who have lost loved ones are asking for longer-term treatment programs, reduced criminalization for drug users and increased sentencing for drug dealers.

Some of the local programs have been lacking due to the lower numbers of people affected in Wayne County in comparison with other areas in the state, Madden said.

Efforts are underway to refocus the mission and work of the local Substance Abuse Task Force, which includes members from different organizations in the county.

Some of the programs Madden would like to see develop in Wayne County include increased efforts to secure funding to pay for naloxone, an opioid antidote used during an overdose, so it can be more easily distributed in the community.

Also, increased syringe-exchange programs and the start of a criminal diversion program, similar to the Hope Initiative in Nashville.

The Hope Initiative, based out of the Nashville Police Department, allows anyone to enter the police department, turn over their drugs and not face any criminal charges. The program allows people to ask for help and they are sent directly to a treatment program. The program has documented success and is already being modeled in other North Carolina communities.

Madden believes treatment programs are more promising than jail time.

"When you put someone who is addicted to drugs in jail, you haven't changed anything," he said. "They're still addicted to drugs and they're going to try to use drugs in jail.

"You haven't created a public health solution. You want to get people in treatment, not incarcerated."