Library commemoration inspires local recollections of Pearl Harbor

By Steve Herring

Published in News on December 8, 2016 10:00 AM

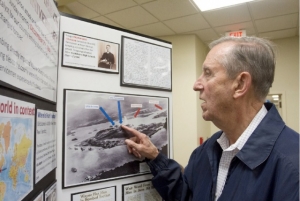

News-Argus/STEVE HERRING

William Teague points at a photograph on display during the Wayne County Public Library commemorative presentation on the attack on Pearl Harbor.

An 11-year-old William Teague didn't really know what to make of what he had just heard on the radio.

But as he and his brother sat in the back seat of the family car on the way home that December afternoon in 1941 he heard his parents talking. They knew that their older son, Norwood, 23, was somewhere in the Pacific, possibly at Pearl Harbor, serving aboard the battleship USS Tennessee.

It would be nearly two weeks before they learned that he had survived the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Those memories and more came flooding back to William Teague Wednesday night as he listened to a program held at the Wayne County Public Library commemorating the 75th anniversary of the attack.

Jeff Bockert, the state's east region supervisor of historic sites, laid the foundation of the political and military climate leading into the attack. He then carried the audience of more than 50 people through an almost a minute-by-minute timeline of the battle.

Displays featured photos, maps and clippings from the News-Argus about the attack as well as biographical information on some of the Wayne County men who were at Pearl Harbor.

Teague said the program was a very thorough lesson, and that he had learned more than he had previously known about the attack.

Norwood Teague was a 1934 graduate of Goldsboro High School, but the family had moved to Raleigh in 1938.

"We were in Sanford at my uncle's house when somebody came running up on the porch and said Pearl Harbor had been bombed," William Teague said. "Of course my folks knew he was at Pearl Harbor or in the Pacific. So we cut the radio on, you didn't have no televisions. So we listened to the radio. Of course coming back my mother and dad were talking to each other, and me and my brother were in the backseat.

"It was about two weeks before we heard from him, just two lines. It said, 'I'm OK. They asked for it, and by golly we are going to give it to them,' talking about the Japanese. He fought fires for a while, and then finally got everything under control. The West Virginia was outside of them. They (Japanese) came across the water and brought the torpedoes. They (Tennessee) were protected. The Arizona was sitting right out where it got everything."

People were gun shy after the attack, Teague said.

"My brother took his fire brigade over this island here (Ford Island)," Teague said. "He was running along somewhere on this side of the island to get his fire extinguishers filled back up again.

"Somebody said, 'Halt. Who goes there?' Everybody was scared that the Japanese would invade. He said, his voice went up about three octaves, 'Ensign Teague.' He scared him to death."

Teague said his brother kept a detailed journal of his time aboard ship even though he was not supposed to.

"He was telling what they had to do -- pick up bodies and everybody had to get to the hospital that needed to go," Teague said.

"The West Virginia burned, and it was leaning over on them. His skipper, who was the officer in charge, turned the props on and the wake kept the burning oil off of them. So they had damage, and they had to get themselves fixed up to some extent, and then they went to Washington (state) for general repairs (to the Tennessee)."

The West Virginia, that was berthed next to the Tennessee, was one of the first ships to be hit.

Onboard the West Virginia was Marine Jim Dixon of Wayne County, Bockert said.

Dixon was on deck around 8:10 a.m. Hawaii time when a modified Japanese armor-piercing 15-inch shell penetrated the Arizona's forward deck plunging into a magazine causing an explosion that instantly killed more than 1,100 men -- nearly half of the 2,400 fatalities that day, Bockert said.

A huge fireball went 110 feet into the air, he said.

Chunks of steel bigger than automobiles rained down on them.

"He said he had to hide underneath a (gun) turret on the West Virginia to keep from being hit by them."

All of the ships hit that day with the exception of the Arizona, Oklahoma and Utah were returned to service and saw action in World War II, Bockert said.

Also, the U.S. sank every single Japanese ship that participated in the attack, Bockert said.

Teague had been on the Tennessee for a year and a half prior to Pearl Harbor. He remained onboard for another six to eight months before being transferred to the U.S.S. Essex, an aircraft carrier.

"He saw more action with that than he did anything else," Teague said. "He was in all of the battles in the Pacific with that. The worst thing was the kamikaze planes. They dodged kamikaze planes, but one hit the ship."

While on the Essex, Teague continued to keep a journal that ended up filling 12 books.

"He left it on the ship for the library," William Teague said. "He got it back. Five years after the war was over a box came, and it was all of his journals."