Former POW speaks to SJAFB airmen

By Kirsten Ballard

Published in News on February 5, 2015 1:46 PM

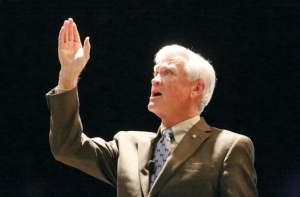

News-Argus/MELISSA KEY

Barry Bridger describes what life was like for him as a prisoner of war in Vietnam to a crowded auditorium of airmen at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. Bridger went back to flying soon after this experience and completed a tour at SJAFB.

Barry Bridger was missing in action.

He was listed as possibly killed in action.

In 1967, his plane went down over Hanoi, Vietnam.

His missile jammer failed. The explosion that followed blew off the tail, right wing and half of the left wing and engulfed the F-4 fighter jet holding David Gray and Bridger in a fireball.

And for the next seven years, they disappeared.

Standing in front of a packed theater of service members at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base on Wednesday, Bridger recounted his time as a prisoner of war in Vietnam from 1967 until 1973.

His speech was part of the leadership series aimed at inspiring service members at the base.

He spoke twice, both times to standing ovations.

During his time in Vietnam, Bridger was recruited for the BOLO II mission. The planes were equipped with a new pod, designed to jam the guiding device on missiles.

"The scientist said, if the pod doesn't work for some reason, fly up next to your element leader and his pod will jam for both of you," Bridger said. "Seven years later, I came home and was briefed by the same scientist who said, 'Do not fly next to your element leader because you'll double the reflective energy and be shot down' -- duh."

Bridger described his time behind bars by periods. The first was from 1964 until 1965, when there was no torture. However, starting in 1965, the government began a period of POW exploitation.

Bridger says the environment of abuse and torture lasted for years.

His captors wanted military information, propaganda and him to repent for his war "crimes."

His shoulders were popped out of their sockets. Even to this day, he has neuropathy from having his extremities bound with ropes until the circulation was cut off.

But even under duress, Bridger said 100 percent of the Americans would rather go to the torture chambers than confess.

He skirted over the details, instead laughing about his cellmate dropping his toothbrush in the bucket they used as a toilet -- "Bristles up?" he asked.

He told them about how the prisoners learned to weigh themselves using water displacement.

It was a story of triumph.

"To provide perspective, let me ask three questions," he said. "Was it ever in accordance with the Geneva convention? No. Did we ever see the Red Cross? No. Did we have men going legally blind from lack of simple vitamins? Yes."

But in the camps, the prisoners created their own culture, family and set of laws. Every day was combat, Bridger said.

"You quickly learned not to focus on the final score, but only on the play at hand," he said.

Through code, the prisoners shared information by tapping on the walls. Many POWs returned to school after the war, acing final exams in subjects they never studied.

"All of which they learned by pressing their ear against a 3-foot thick concrete wall and tap-tap-tapping in POW code," he said. "Never underestimate the power of the human spirit."

The government wanted to separate them, divide their strength and destroy their culture bonds, Bridger said. Instead, the men fought every day for the right to worship in their rooms. They laughed and joked. Each trip to the torture chamber was a chance to complain about the food or the weather.

It was four years until Bridger's name was released as a prisoner of war. He says his small hometown of Bladenboro went bonkers when it heard the news.

Five years in, he sent his first letter to his brother and sister-in-law.

And after seven long years, he got to go home. Flying from Hanoi to the ocean, he remembers the silence.

"A target that big is pretty easy to hit," he said. "You could hear a pin drop... eventually we heard the mic cut on and the pilot said 'We are feet wet,' and the party began."

Two weeks later, Bridger returned to service.

"I went back to work, that's what you're supposed to do," he said.

In 1973, he was assigned to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base for four years as an instructor pilot. In 1984, he retired.

Looking back, he says his favorite part of his time in the Air Force was the quality of people he served with -- quality reflected by the men and women of service today.

He ended with a question.

"What, pray tell, would you have done, under the brutal pressure of the Hanoi prison?" he asked the silent auditorium. But he says their behavior is predetermined by who they are now.

"You are what you value," he said. "If you enter into a period with great tribulation and focus on yourself, you are very likely to come out more self-centered. If you enter into a period of great travail and focus on ideas more meaningful and valuable than yourself, ultimately more human, ideas such as faith, family, service to others, then you are very likely to come out with a deeper and more profound commitment to these enduring lifestyles."